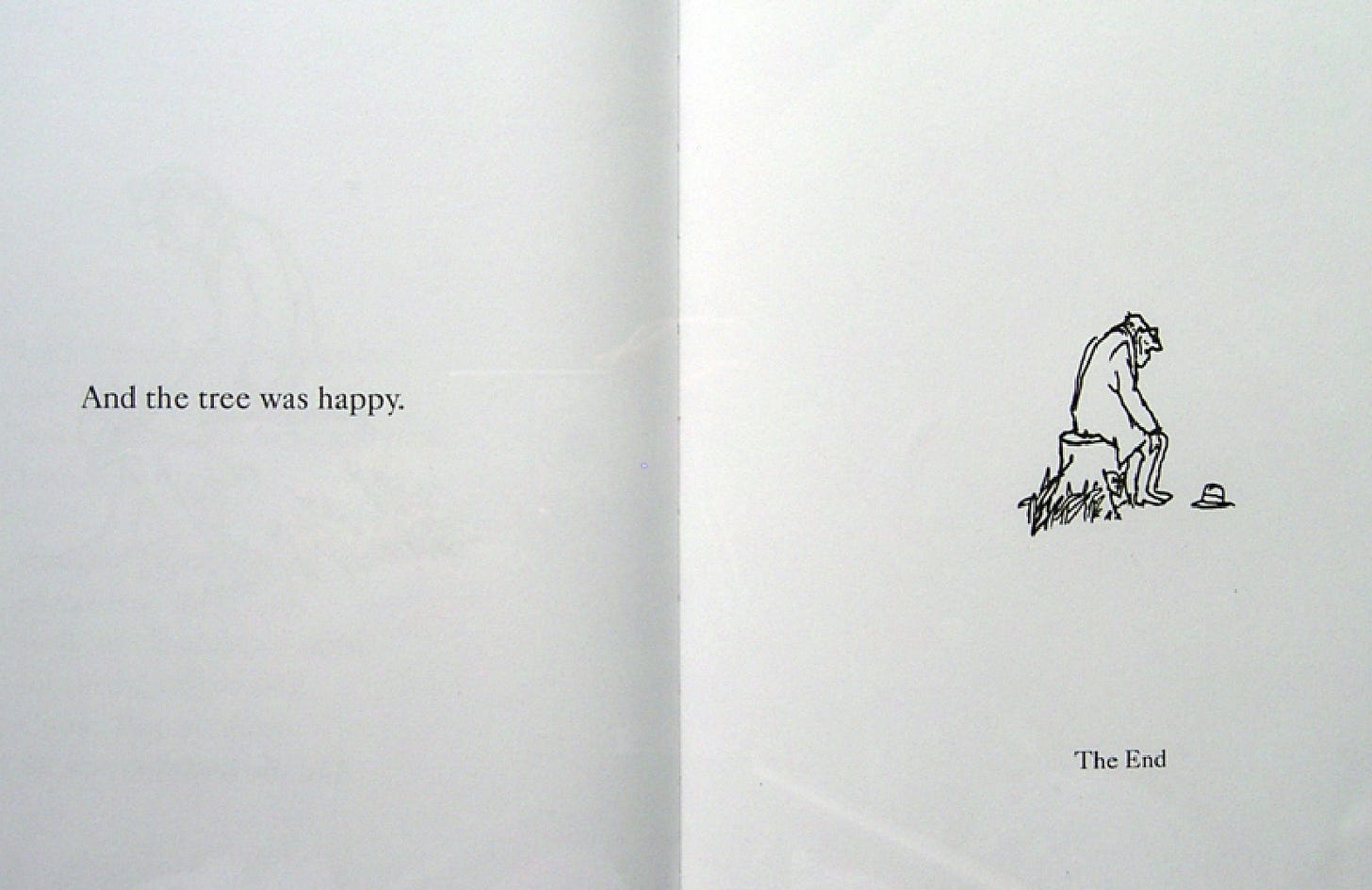

And the tree was happy…

This is how Shel Silverstein’s picture book The Giving Tree begins.

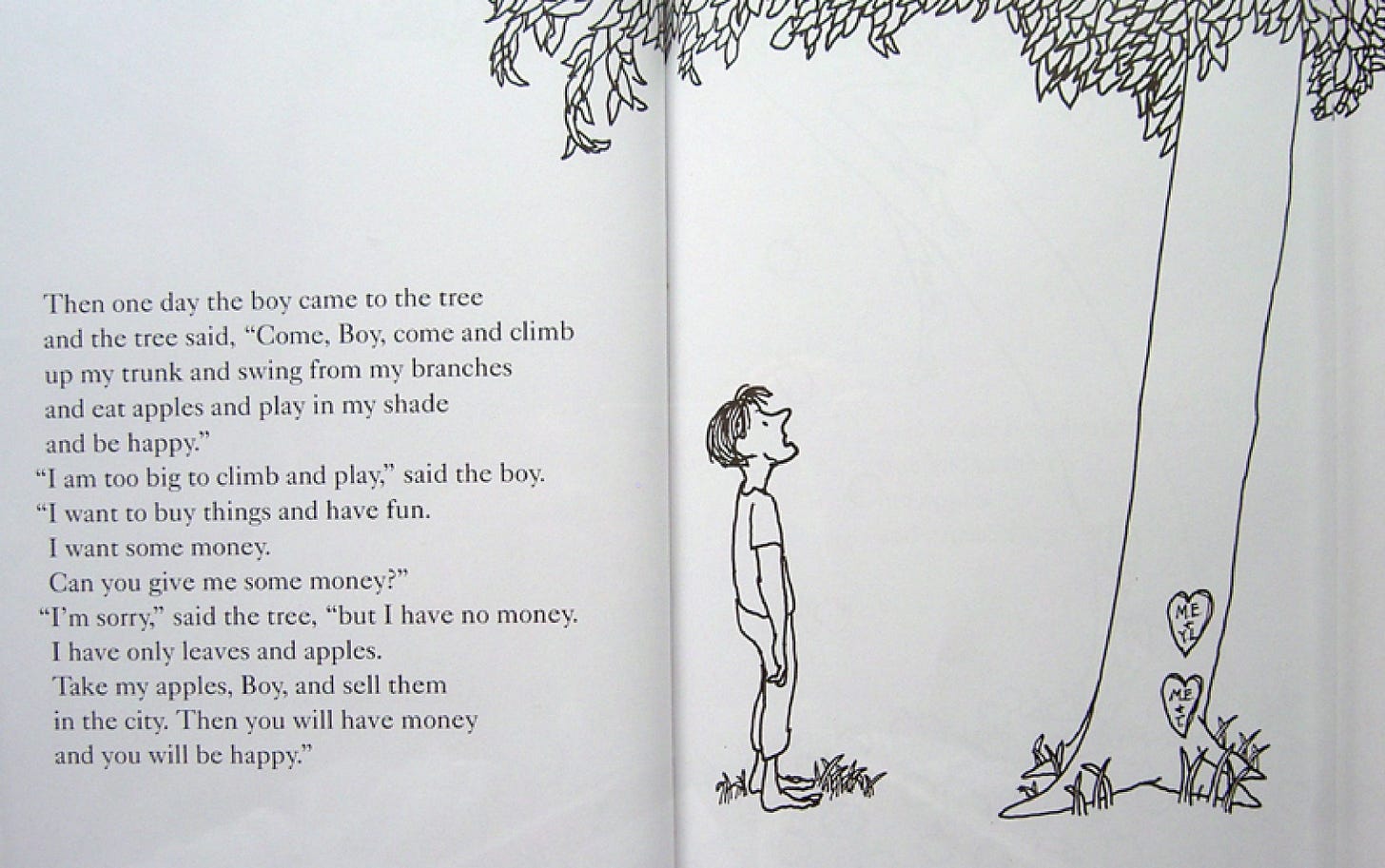

Silverstein tells the story of a tree and a boy. The boy enjoys playing with the tree—swinging on her branches and eating her apples. Their relationship was free and loving. But, the boy grows up and grows distant. Then, less out of love and more out of brute, material desire, the boy, now a man, asks for money. (Though, he is still called a boy.) So, she gives him all of her apples in the hopes that this makes him happy again (for he does not seem very happy anymore)—and giving him what he wants makes her happy.

Then, older still, the boy comes back, of middle age, and wants a house so he can raise a wife and kids. The tree gives him all of her branches.1 And she is happy, for she gave him what he wanted.

Then, as an old man, the boy wants a boat that will take him away, and she offers her whole trunk. He chops her trunk down and lugs it away. It is only then, when he has taken everything from her, that she is not happy.

He comes back one the last time, frail and tired, and he doesn’t want anything she could offer him before—not her apples, or branches, or trunk. He simply wants somewhere to rest. He “doesn’t need very much now.” So he sits on the tree, now nothing but a stump, and the tree was happy.

This story presses us to ask how it is that we take and how it is that we give. When we do so, are we giving away too much of ourselves? Does that make us happy? Does it even make the person taking happy? How do we guarantee that our relationships of exchange are free, loving, and thoughtful, instead of being built on ill-conceived desires and obligation? The boy at the start and end of his life loves the tree for what she is and what she can naturally give. Their relationship is defined by mutuality, by a fitting reciprocity of their needs. But the work of their relationship in mid-life is riddled with that uneasy, maternal generosity—the running ragged and running thin; giving from lack, not from abundance.

So, what makes for a good gift?

Your acquaintance is getting married. Invited to the bridal shower, you are neutral, but easily swayed into tagging along because your best friends will be in the troupe. One thing though: you have to bring a gift. At the mall, alongside its typical terrors, you see a book that purports to be about how to cook a variety of bite-size, dinner deserts. Not thinking about whether the bride would like that sort of thing, you buy it, get the gift receipt, and toss it in your purse.

Again, it is Christmas. Alongside its usual horrors, this time some of your third cousins will be there. You have never met them. You are told to buy them gifts. You don’t know the first thing about them, but any attempt to shirk the request is met with trenchant and furrowing passive-aggression. You buy some kitchenware and stationery and call it a day.

Again at the office party, then again at the birthday party, and again, and again…Events roll up throughout the year where you must give someone a gift. It is not really about you. It is not really about them. In his article “The Gift” Clive Dilnot calls this obligatory exchange, swarming with resentment, the transaction of the gift-article.2

The true gift is different. The true gift finds its best expression in someone freely finding or making something for their beloved pal. The giver discovers a double joy in this. First, there is the pleasure of pleasing another; you learn what they want and need, what’s on their mind, their quirks and character, and it feels good to see them satisfied through your attention; second, there is the pleasure in finding just the right thing, an object that perfectly fits the bill, that screams out their name.

The receiver finds a double joy in this as well. First, most obviously, the friend gets what they want. “Oh my god! I’ve been looking for something just like this forever!” Perhaps, most specially, this joy is met with a sort of self-discovery, wherein you didn’t even know that you needed it. Second, there is the joy of recognition: “I feel so seen!” This is the satisfaction of thinking about the time they spent thinking about you; your friend spent time imagining you opening up potential gifts, seeing your reaction, until they knew what would bring you the most joy.

The gift is not a mere thing, but a symbol of love and recognition between two people, and a sign of tender effort and time spent.

The gift-article is simply the market-manifestation of the fact that we are put in situations where we ought to give a gift, but do not want to do any of the imaginative work. When we, in fact, don’t even want to give a gift. It is a sign of expenditure, and nothing more. The scenarios of pseudo-giving arrive to us as stuffy and alien requirements. This situation is worsened by the economic pressures teaching us that we do not have what we need (and buying something will fix that)—that your world of things is scarcely enough—and that you must buy more than you need (for this is freedom). One must be spendthrift and gluttonous. The only meaning of the gift-article is the price tag.

Gift-articles come in two varieties: the “relentlessly practical” and the useless. Basically, when you don’t actually want to give someone a gift, or someone you don’t know “requires” a gift, then it will either be a frying pan or a book that isn’t meant to be read.3 This guarantees that the relation will spurred by resentment and obligation instead of freely imagined love.

Why is this? What made the difference between a world full of gifts to ones full of substitutes?

Dilnot evinces two primary reasons for the atrophying of our gift-giving practices. First, there are just more situations today where you must give a gift to someone when you do not want to. Second, the market responds like water to cracks in the pavement and sensed this need: the need for something that was like a gift but that wasn’t really a gift—something to merely buy and hand over. The gift-article is an economic substitute for personal gift-giving relations. As Dilnot puts it, “a generalized culture of gift-articles marks the existence of a formal but not a substantial relationship to the other.”4 We simply have more relationships that are purely formal and empty now.

Dilnot takes the gift-article to be a reflection of, and evidence for, the larger trend in the industrial creation of objects wherein the process of their design and creation has nothing to do with actual people’s relationships.5 Products are considered possessions (for consumption, ownership, or display) or commodities for exchange.6 But these the objects around us can also be considered dialogically, as physical avenues to promote welfare and maintain (or change) relationships. This dialogic relation between people and objects is one in which people consider how objects can be made more beautiful and useful in our shared lives. So, one can train yourself to see objects not as mere stuff, but as so many fulcrums upon which we exercise our creativity and imagination toward bettering our relationship to the world and each other. In other words, we make objects to stay alive, to live pleasantly together, and to create a world that reflects us. Objects can enter into a dialogue with us; they are external opportunities for reflection on what is good for us and, by extension, for the people with whom we share a physically, intimate life with.

The world-making function of gifts (or gift-articles) can simply be a matter of dressing, feeding, and sheltering ourselves, or of alleviating some deficiency; lightbulbs help us see in the dark and chairs allow us to rest after standing too long. Gifts make up our worlds—if we are giving well—in a way that reflects our needs, our awareness of our needs, and visions of a well-lived life. Since gifts are physically in the world, they can serve as further objects of reflection. When you notice a chair, you can then ask, “Does this allow me to relax and relieve pressure from my feet and spine? Should this chair be here or somewhere else?”

Besides objects (potentially) clearly reflecting our needs and awareness, objects “function or work is giftlike in that its form embodies recognition of our concrete needs and desires.” (58) Objects should be well-designed such that they ergonomically and obviously teach us ways to live better. Products should clearly represent their usefulness and beauty. (People and products alike will hide themselves to the extent that they are useless. Vagueness in presentation is a good sign of a worthless, sophistic object.) Gift-articles are often indiscernible as sources of recognition. One looks at it and thinks, “This is junk. Who would need this?” We can’t imagine a good life with it because it wasn’t made with that in mind. It was, by definition, not made with any particular person in mind. Often, it is made to make money, or was altered to increase efficiency, and not with anyone in mind.7

We make objects and objects make our world up. Whether or not this relationship is grounded in our actual desires, relationships, and ideas of beauty is up to us. Dilnot hammers this point in:

All commodities, all products, are subject to an act of choice as to whether they may potentially function as a true gift. This implies that the difference between "gift-objects" and products is not a difference of types of object, but of the conditions of things (which includes the conditions of how we receive and understand things to be). Most, if not all, gift-articles are not gifts in this sense. Equally, most mundane objects contain (or may potentially contain) a moment of the "gift" in the second, better, sense of the term. (61)

Objects are necessary for securing our survival and doing so pleasantly.8 Objects make up our world. We, then, have a role and a responsibility to engage with this world of objects such that it doesn’t debase us and instead reflects our needs and our tastes. We must view objects, as much as we can, as gifts and not as gift-articles: as something connected and responsive to the world we want and need. Otherwise, life will simply be full of meaningless garbage.

We, too, are objects to be augmented and designed, sensible and changeable. Make of yourself a gift, too. Otherwise, one day, you’ll find that you’ve become a gift-article, shuffled about by laws and markets, without a sense of friendship, unrecognizable, and cold like a present bought just for the price tag. To be a gift is to recognize your own needs and the needs of others, and to make this as clear as you can. Accept the gift you are to love the gifts you are given.

Freely and with you in the mind,

Nicholas

What the fuck kinda house you gon’ build with branches? Anyways.

Dilnot, Clive. “The Gift.” Design Issues, vol. 9, no. 2, 1993, pp. 51–63. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511674.

Perhaps, even, when one does not want to receive a gift, the same logic applies.

p. 53

p. 54

p. 55. Dilnot’s forays into political economy and later his lampooning of deontological and absolutist ethics is sloppy and completely unearned. But I don’t feel like critiquing him. I’m just here to talk about his insights. Also, whenever folks like this do economic-chatter, it is not empirical. At least nothing is cited. It just reads as literary Marxism. This is not good. One should cite actual economists when one discusses the economy. Alas.

Not that making some process more simple and efficient is bad. And not that creating wealth is bad. But just because a number goes up doesn’t mean life gets better. That requires reflection.

This language that I’ve been using in this post—“securing survival,” objects as sources of and expressions of our ideas of the good, etc.—and most of my thinking so far about everyday aesthetics, come from Janet McCracken’s book Taste and the Household. Post on that delightful book at some point down the line. Probably in a month or two. I’d like to do justice to it, so this post seemed to be good practice. (She uses Dilnot’s concept of the dialogic nature of objects quite a bit.)

Hi Cara!!!! Hope you are fabulous!

Love this book🙂Great post. Hugs!